In May 2024, the UN General Assembly adopted the resolution designating 11 July as the International Day of Reflection and Commemoration of the 1995 Genocide in Srebrenica.

In 2020, the War Childhood Museum launched a landmark partnership with the Srebrenica Memorial Center to document the experiences of those whose childhoods were shaped by the Srebrenica Genocide. This collaboration represents the first systematic effort to preserve testimonies and memories of the genocide from the perspective of children.

Here are some of stories from the compiled collection.

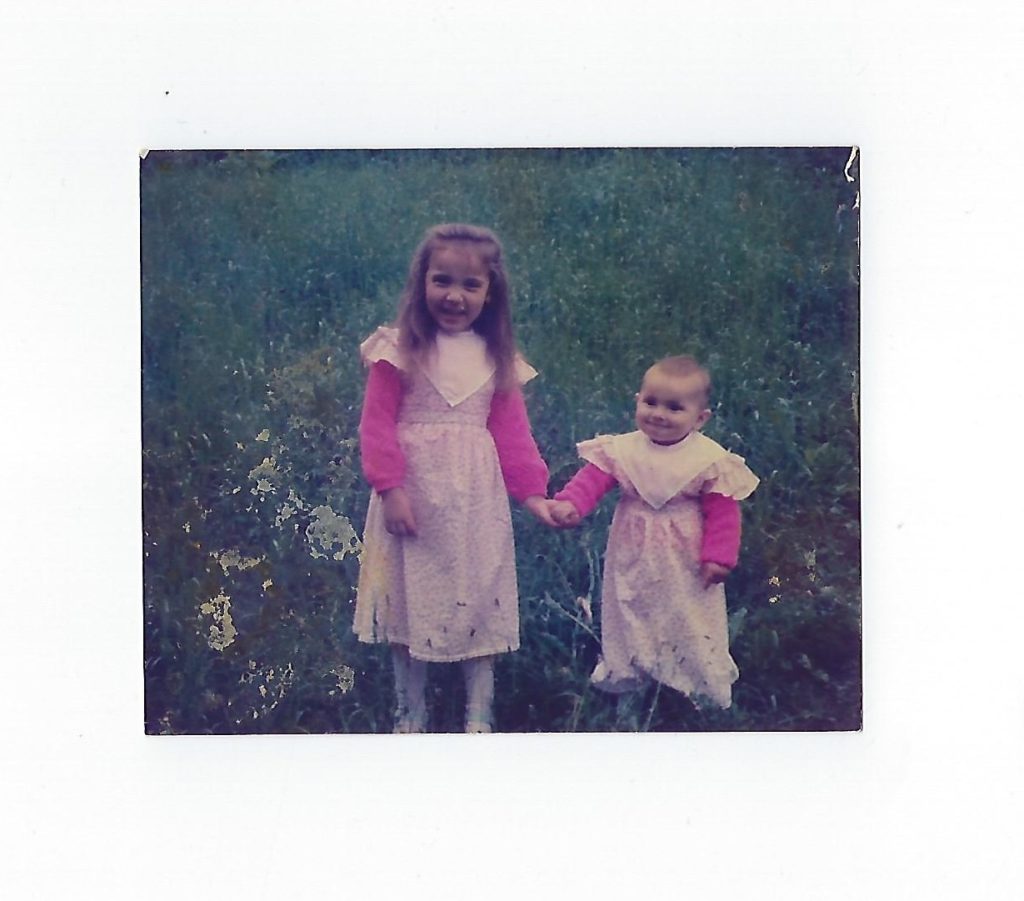

My Sister Jasna

Although it was formally considered a demilitarized zone, shellings and shooting were common in Srebrenica. On the 25th of May, 1995, a shell struck right above our house. I remember the massive detonation, the noise and the blinding dust. We all ran outside, and as we did we realized that my younger sister Jasna wasn’t with us. My mom quickly went back inside to find her, but she came out crying, carrying Jasna in her hands. A piece of shrapnel had hit Jasna in the head, and she didn’t survive. She was killed eight days before her tenth birthday.

These photographs were taken in January of the same year.

Alma, born 1982

Dimije – A Gift from My Brother

I was fourteen when the war started, and all of my old clothes became too small. I had two younger sisters and two older brothers who lived with me at the time. One day this woman came by the house looking to barter a pair of traditional trousers dimije for two kilograms of flour. My brother Almaz Tursunović, who was seventeen years old at the time, decided to buy them for me. The first time I washed the dimije, a shell landed next to the house and shredded them. My brother disappeared when Srebrenica fell, and I left for the rest of the world. The dimije travelled with me to America, and now they are back home in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Sadika, born 1977

Knitting Needles

These knitting needles were made by my uncle, from parts of an umbrella frame. It was with them that I learned how to knit during the war, and knitting was a way for me to play and amuse myself. Together with my mom, I learned how to knit a flower, a scarf, and clothes for my baby doll.

Fleeing Srebrenica, my uncle never made it to the free territory and was never found.

Edita, born 1984

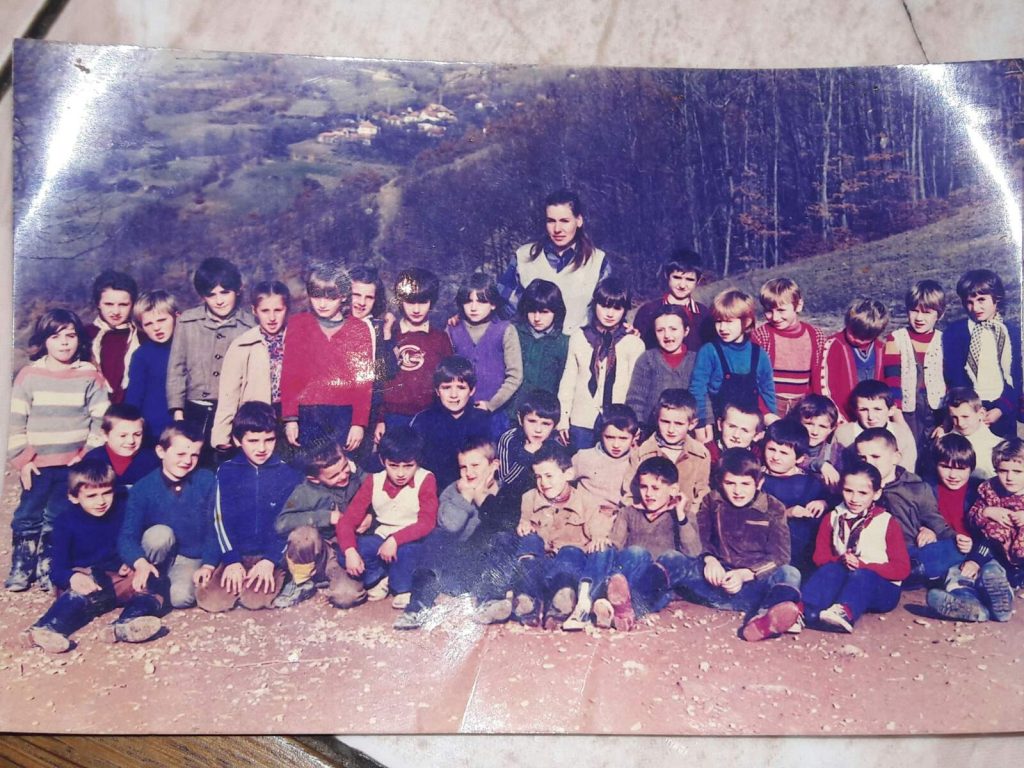

The School Photograph

This photo was taken before the war, when I was in the first grade of a village primary school in Beširovići. There were forty-two of us in the classroom back then.

Many of my schoolmates were killed during the Srebrenica genocide. I received this photo as a gift after the war, and I have kept it as a memento of them and of better times.

Ismail, born 1978

Father’s Razor

My father was a teacher, always clean-shaven and neatly dressed. As a child, I often watched him shaving and getting ready for work.

He didn’t survive the Srebrenica genocide. My mother and sister brought this razor in the bag they carried while leaving Srebrenica—I looked after it with care for many more years.

Whenever I tried to use the razor, it would bring back memories of my father and his boundless love for my mother, sister, and me. I know I would never be able to use it as skillfully as he did, so I am giving it to the Museum for safekeeping.

Emir, born 1979

The Doll Without an Eye

We arrived at Potočari on the 11th of July 1995, part of a river of people flowing into the city that day. Our time in Potočari was characterized by bustling crowds and hopelessness. We spent two nights out in the open, and then, on the 13th of July, all of a sudden, people around us stood up and started running. We moved toward the buses at pace. I gripped my mom’s traditional trousers tightly with one hand, and held my doll with the other. The doll was missing an eye, but it was my favorite. Hold on to Mom and don’t let go! It seemed, at the time, as though my mom’s trousers were an umbilical cord keeping me alive.

We managed to push through to the rear door and get onto the bus. As we passed through Bratunac, people spat at us, threw rocks and cursed at us. Not long after that the bus stopped. A young soldier– tall, with a long thick beard and shoulder length hair – entered the rear door of the bus. He only had military trousers on. He held a knife in one hand, and a large rifle in the other. He yelled: “Hand over all the gold, silver, money, anything of value you have on yourselves!“ Everyone was quiet. As if I was alone on the bus, I stood up and yelled: “Please, take my doll, I have nothing else to give. If you want, you can take my doll, will you?“

I don’t remember if the soldier looked at me. I only remember the great fear I felt. We heard the bus driver telling him to get out. Then the bus was on the way again. My mom was hugging me tightly, and I was hugging my doll.

I held on to my doll for a while, but somewhere along the way I realized that I had lost it. I had bigger, prettier dolls later on, but she always stayed in my memory as the doll with the missing eye who saved my life!

Almasa, born 1986