The War Childhood Museum’s collection is built from personal stories and objects shared with us by individuals from around the world.

To better understand what the Museum represents to them—and what inspired their decision to contribute—we launched a series of interviews with collection contributors. Some of the previous conversations are available here.

In this edition, we spoke with Amila Gačanica, originally from Sarajevo and now based in the United Kingdom. Below, she shares her story and reflections.

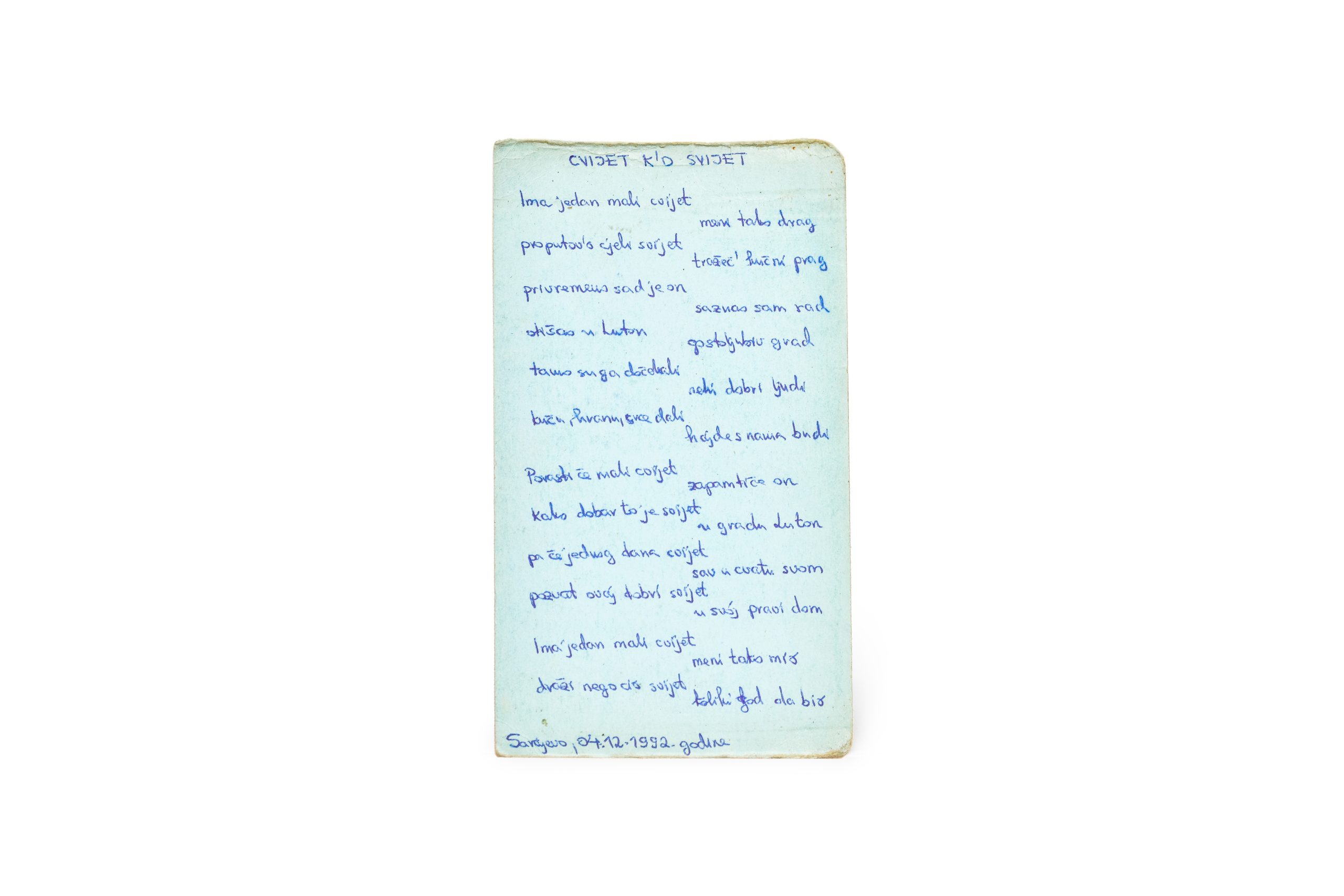

My Father’s Poem – “Cvijet k’o svijet”

Together with some relatives, I boarded the last civilian plane to leave Sarajevo at the end of April 1992. My parents stayed in Sarajevo.

We spent the first month in Serbia, before leaving for Macedonia. From there, we went on to Croatia, where we stayed in a refugee camp for some time. In the camp, we met a missionary named Ashley, who offered to help us get to the UK. I still remember an incredibly stormy evening spent running around and collecting stones to help secure the tent so it wouldn’t fly away; after what felt like just a few minutes of this, we decided to leave the camp and come to England.

We traveled by bus from Croatia to England with around 20 other refugees. Upon arriving in Luton, we received toys, clothes, and food. Very soon after that I began attending school, where I first had to learn English to be able to follow the lessons.

I did not see my mum until 1994, when she joined me in London. My father was still in Sarajevo, looking after his mother who was bed-bound from before the war. We stayed in touch through letters. I have kept and preserved those letters ever since.

After my father passed away, I was going through his things and found this poem, “Cvijet k’o svijet”, which moved me immensely. I had never known that my father wrote poems. In memory of him, and his undying love for Sarajevo, I decided to donate it to the Museum.

Amila, 1985, Bosnia-Herzegovina

How did you come to be a contributor to the Museum’s collection, and why did you make that decision?

In 2019, after my father passed away very suddenly, I was going through his possessions and found a poem he had written about me leaving for the UK during the war, while he stayed behind and joined the Bosnian army. I was in awe of the creativity and tenderness in his words, picturing him on the cold 4th of December 1992, in unimaginable circumstances, writing those lines on a simple blue piece of card.

When we think of soldiers, we often pair that image with strength and bravery, but we rarely get a glimpse into their emotional world. This poem revealed his vulnerability, his love, and his hope. In one verse, he wrote: “one day the flower, now in full bloom, will invite these good people to its real home” (pozvat ovaj dobri svijet u svoj pravi dom) — expressing such a deep belief that peace would return.

I felt it was important to share this vision of him through the War Childhood Museum, so that more people could read his words and see Sarajevo not only for its suffering, but also for its beauty, resilience, and spirit. My father was a true Sarajlija [a person from Sarajevo], and I can think of no better place for his love of the city and of Bosnia and Herzegovina to live on.

In a world still so divided, I also see this as a quiet homage to a time when refugees were received with greater acceptance and humanity.

Do you think your story has similarities to the stories of children who are going through war and conflict today? Why?

My personal story is one of the fortunate ones. I escaped Sarajevo on the last commercial flight out in 1992, at a time when the world was far more open and welcoming to refugees. In the UK, I mostly experienced warmth and tolerance, and over time I was able to “fit in.”

But I know that refugee children today, fleeing wars and conflicts across the world, will face many of the same challenges I did — the shock of displacement, the dissociation, the struggles with identity and culture that so often mark the first generation of immigrants. I remember seeing a photograph when the war in Ukraine began — a young girl saying goodbye to her father. I burst into tears. Not only because I had lived that same moment as a child, but because now, as an adult, I could understand more deeply how her father must have felt too.

For me, the hardest part was growing up torn between two very different cultures and ways of life. I longed for a Sarajevo I never really got to know beyond the age of six, yet was often judged or questioned for still calling it “home” instead of London.

Over time, I came to realise that even when everything is different, we carry home within us. My mum made sure of that: she created a Bosnian home wherever we were. Our friends experienced her hospitality, the taste of zeljanica [a Bosnian spinach-and-cheese pie], the refusal to accept “I’m not hungry,” and the ritual of taking their shoes off at the door. What once felt “different” became a source of pride.

If anything, I hope my story can show how powerful — and healing — it can be to call two places on this earth “home.”

What do the War Childhood Museum and similar initiatives mean to you?

They are sacred spaces of memory. They give voice to people’s stories and experiences, and in doing so, they allow us to witness, to release, and to honour the tender, human moments that often arise in the hardest of times.

For me, the Museum is not only about preserving history — it is about educating the present. It is vital that children who grow up in safe and secure circumstances learn to be compassionate and open-hearted toward those who have been forced from their homes. This is how we ensure refugee children are accepted for who they are, and for all they have endured.

These children will one day be our leaders. I pray they will build a more humane and compassionate future than the one we see today.