The War Childhood Museum’s collection is built on personal stories and objects shared by individuals. Through interviews with the collection contributors, we look into what the Museum represents to them and what inspired them to share their testimony or donate an object.

Ahmad Sawas Najjar is originally from Syria, which he left due to the conflict. He now lives in Belgrade, Serbia, where he graduated from the Faculty of Law.

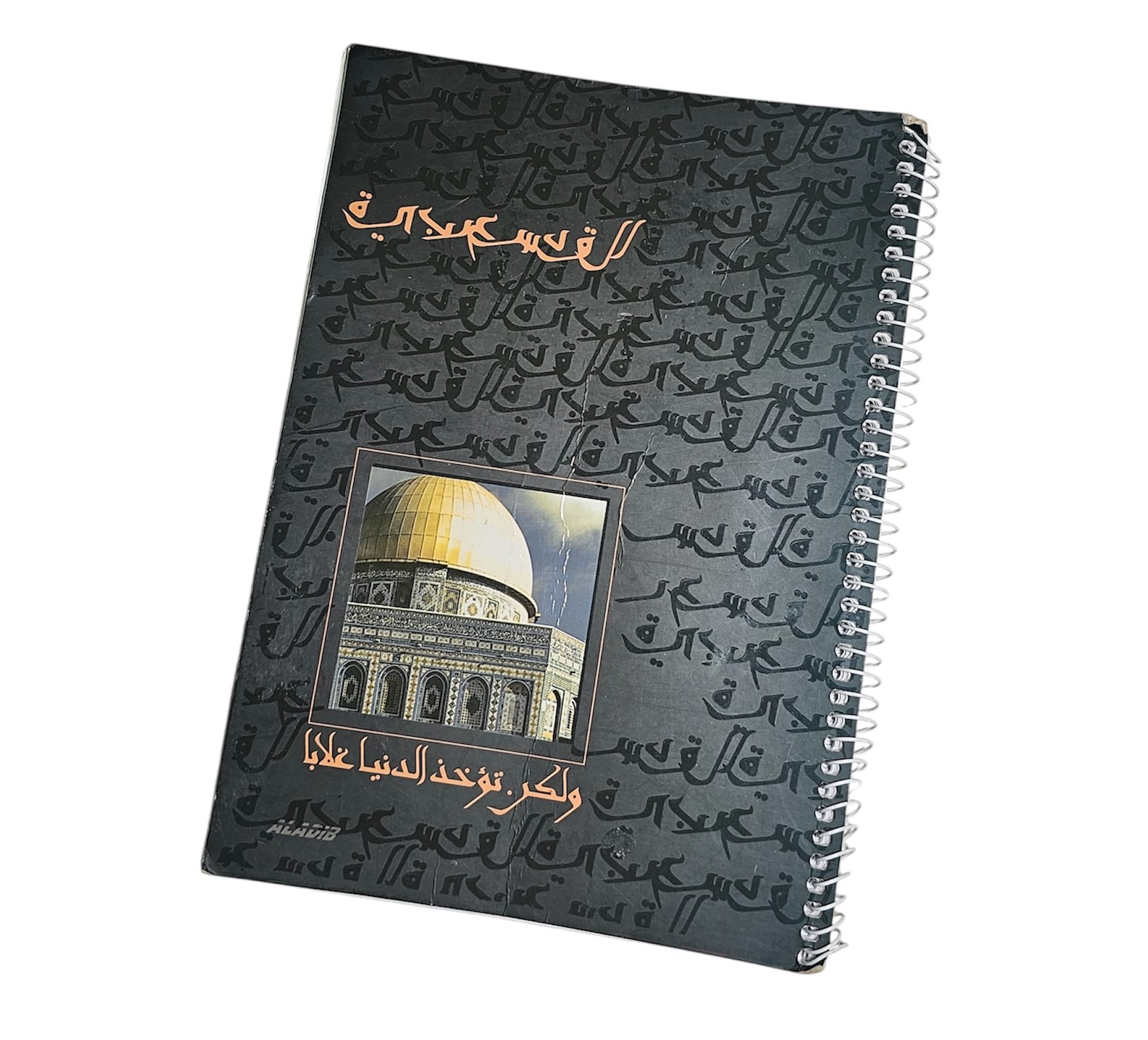

Photo: Personal archive, Ahmad Sawas

Although he is integrated into his new community, Ahmad still carries with him memories of Syria. One of the most meaningful, a special notebook, he chose to donate to the War Childhood Museum for safekeeping. Read the story behind the notebook below, along with an interview with Ahmad.

The “Jumble” Notebook

This notebook is one of the very few personal items I took with me when I fled Syria. It was the last school notebook I used, and I used it for everything — from religious studies to mathematics. In addition to schoolwork, I also noted down details related to a small store I was running at the time, as well as my first love poems, written as a teenager.

It holds traces of different chapters of my life: school days, work, and early attempts at expressing myself through writing. That’s why I decided to take it with me when I left Syria, and I continued to keep it safe after arriving in Serbia in 2011.

Today, I live in Zagreb, and The Jumble deserves to find its new place — in a museum collection.

Ahmad, b. 1996

Syria

Why did you decide to donate your notebook to the Museum?

I was familiar with the work of your Museum as a place where items from the war are collected—items that belonged to children who lived through the war or fled from it. Stories and belongings of great figures and warriors are often preserved, but one of the most vulnerable groups—children—is rarely talked about. They are mostly mentioned as numbers: ten children killed here, hundreds displaced there, and so on. Rarely are they seen as individuals, as people who carry an entire story with them. That’s why I saw the Museum as a place where such stories can be preserved and shown to the rest of the world.

Do you think your story could be meaningful for children who are living through war today?

It might help them when they see that this was my last notebook from primary school while I was still in Syria. I used it for all subjects—it was a kind of catch-all notebook—even for personal things outside of school. When I first fled, my education was interrupted for several years. Still, I managed to persevere, to continue my education in Serbia, achieve my goals, and graduate from university. This notebook became a kind of symbol for me—a reminder of what was left behind, but also proof that even when life comes to a halt in one place, it can continue and grow somewhere else.

When you think about initiatives like the War Childhood Museum and other projects that preserve the memories of children affected by war, what do they mean to you—personally, globally, or in any other way?

I see them as spaces where the personal stories of children who have lived through war and terrible experiences are preserved. These stories don’t remain just numbers, what they show is that behind every number is an individual with their own story and life journey. Such stories are often best told through personal objects, because they reveal that you’re not just a statistic, but a whole life, a complete story.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.